By Nick Southall, April Sawyer, Sam Diaz, P.E., Chris Hammersmark, Ph.D., P.E., M.ASCE, and Chris Bowles, Ph.D., P.E., M.ASCE

A river and floodplain restoration project in California’s Central Valley is working to undo the ecological challenges caused by decades of hydraulic gold mining. The new riparian and aquatic habitats created will help restore natural river processes, prevent flooding, and improve conditions for native fish.

In California’s Central Valley region, a floodplain and river restoration project is working to turn back the clock on the Yuba River’s gold mining history and reset the equilibrium between natural river functioning and native fish survival. The Hallwood Side Channel and Floodplain Restoration Project is a multiphase, multiyear effort designed to improve habitats in the lower Yuba River for chinook salmon and steelhead trout — members of the salmonid family.

When completed by 2023, the project has the potential to enhance or create as much as 157 acres of seasonally inundated riparian floodplain habitats, more than 1.7 mi of perennial side channels and alcoves, and more than 6.1 mi of seasonal side channels, alcoves, and swales.

This nearly $7 million, multiple-benefit project aims to enhance productive juvenile salmonid rearing habitats to increase the natural production of fall‐run and spring-run chinook salmon and Central Valley steelhead by removing human-made constraints from the river corridor and allowing the project reach to evolve more naturally.

A less than golden legacy

The Yuba River flows through the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada and drains an area of approximately 1,400 sq mi. Historically, the lower Yuba River provided a thriving environment for salmonids. Before the arrival of Western settlers, the Native American tribes of California’s Central Valley, including the Nisenan and Southern Maidu, inhabited the project vicinity and would frequent the lower Yuba River for its abundant salmon runs and favorable climate.

The lower Yuba River, just northeast of Marysville, California, was greatly affected by the discovery of gold in the Sierra foothills in the 1850s. Fortune seekers flocked to the area and used hydraulic mining techniques to indiscriminately wash soils from the hillsides to be subsequently screened for gold. Much of the waste material was transported downslope into streams and rivers.

As a result, hundreds of millions of cu yd of sediments were sent down the valley and into the lower Yuba River. Once out of the foothills, on the lower-gradient waterway and adjacent floodplain, channel velocities decreased as the transported sediments were deposited. These sediments aggraded the channels to depths of up to 20 ft, buried vital habitat, and caused flooding that displaced nearby communities. In particular, widespread accumulation of sediment around the town of Marysville led to decades of flooding.

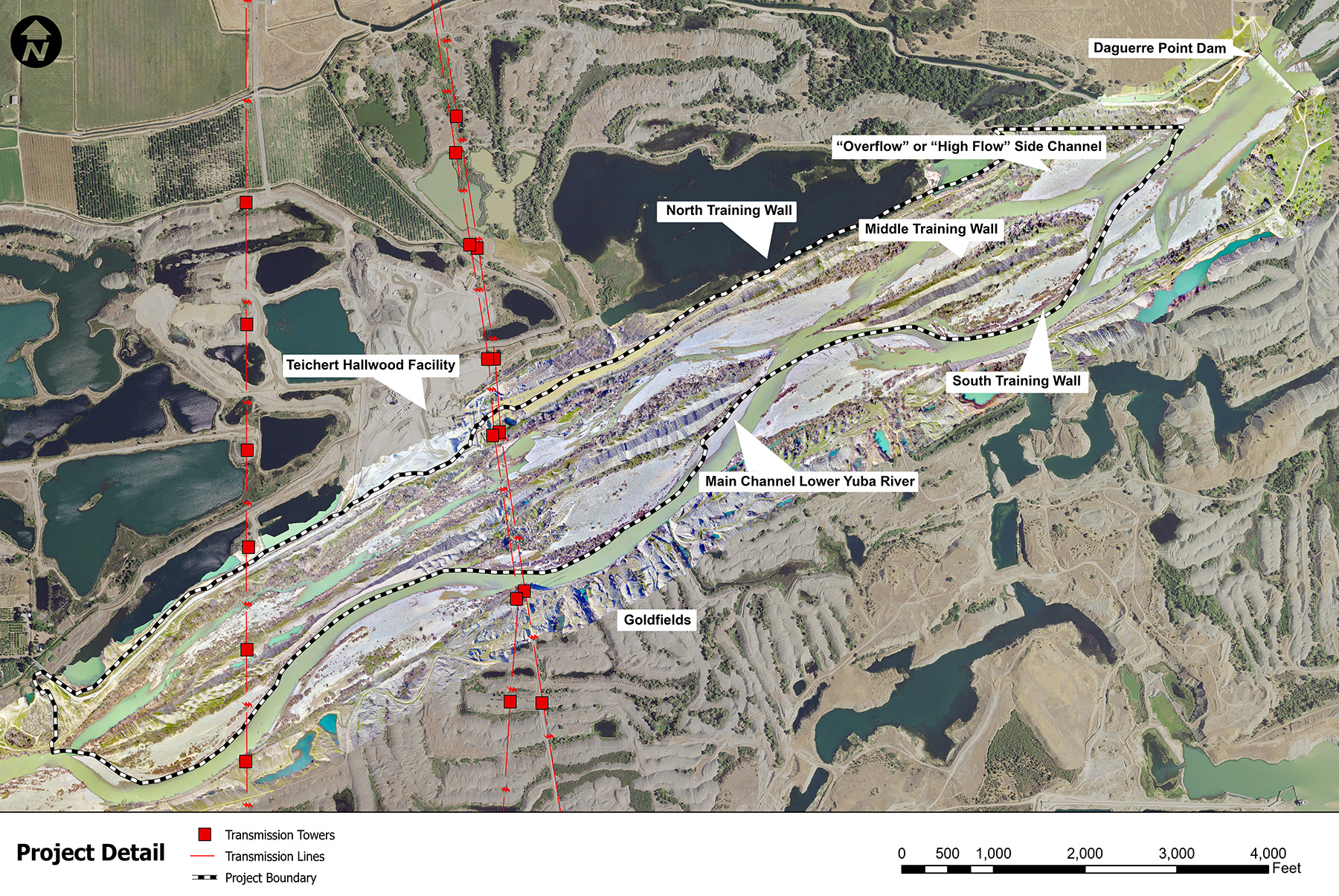

By the early 1900s, the alignment of the river had shifted approximately 1 mi north. Large dredging operations were assembled to rework the deposited material, which resulted in repeated relocations of the river’s course to facilitate access to new areas. At this time, the California Debris Commission endeavored to channelize the Yuba River into well-defined limits and improve downstream flooding conditions. The California Debris Commission hired dredge miners to construct tall linear structures — made from piles of dredge spoils and known as the North, Middle, and South training walls — on the banks to redirect, or “train,” the river’s flow. These training walls measured 30 to 100 ft in height.

The Middle Training Wall is located in the center of the 1,500 ft wide flood corridor and runs for more than 2 mi along the length of the site. It was created to provide an overflow channel in this reach and was a function of the innovative dredge type called a double tailing stacker, used to place the tailings on either side of the channel. Thus, the Middle Training Wall, with an average base width of 300 ft, has two crests because the double tailing stacker dredge made passes in the parallel northern and southern corridors, bolstering both the Middle and North or South training walls simultaneously.

These training walls confined the channel width and prevented the river from accessing historic floodplain areas. River bottoms that once provided a mosaic of riparian and in-stream habitats were further manipulated to meet the various needs of local industry, agriculture, and communities through water impoundments and diversions, flood control measures, and of course, aggregate and gold mining. As a result, the riparian and aquatic habitat conditions rapidly deteriorated, contributing to the historic declines in salmonid populations throughout the Central Valley.

The Hallwood project’s design approach focuses on removing these unnatural constraints, such as the Middle Training Wall, that have separated the main channel from adjacent floodplains and restoring the natural riverine and floodplain processes.

Consultation and outreach with various Native American tribes, either currently or historically located in the region, garnered support for the project, especially because of its goal of enhancing the natural river processes to benefit the wild salmon and steelhead. Outreach with the tribes proceeded as part of the National Historic Preservation Act, Section 106, in consultation with the State Historic Preservation Office.

Consultation included phone calls and in-person meetings, and letters of interest were received and included in the Section 106 consultation process. Tribal representatives attended preconstruction training to educate operators and field staff on artifact identification to protect any unanticipated finds of tribal cultural resources.

Hatching the project

The project reach on the Yuba River is located below Englebright Dam, which was originally constructed for the storage of hydraulic gold mining debris. The lower Yuba River is designated as critical habitat for the California Central Valley spring-run chinook salmon and steelhead trout populations, which are both listed as threatened under federal and/or state endangered species acts.

These ecologically engineered enhancements are targeted to provide rearing juvenile salmonids access to floodplain areas with suitable shallow depths, moderate velocities, food resources, and cover from predators, which are all factors that contribute to enhancing their growth rates. When salmonids can feed and increase in size before migrating to the ocean, they are more capable of evading predators, and their chances of returning to freshwater to spawn and complete their life cycles are significantly increased.

In addition to the ecological benefits of the project, the removal of the unnatural sediment throughout the project reach will reduce flood risks by lowering water surface elevations during a 100-year return interval runoff event by up to 3 ft.

Building partnerships

Essential to achieving the project goals were removing the Middle Training Wall and lowering the floodplain, which required the removal of 3.2 million cu yd of sediment from the river corridor. The high costs associated with hiring a contractor to perform this work initially made the project appear cost prohibitive. However, the project team capitalized on a golden opportunity to collaborate with Teichert Aggregates, of Sacramento, which operates an aggregate mining and processing facility immediately north of the project site.

Historically, Teichert had not been able to mine the Middle Training Wall sediment because of environmental regulations governing the materials situated in the active Yuba River channel. Through a partnership with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, however, the plan to remove the Middle Training Wall to create fish habitat laid the groundwork for securing permits to perform the restoration work.

The project team partnered with Teichert to perform rough grading to remove the Middle Training Wall. By removing the wall, Teichert provided a no-cost, in-kind contribution to the project of approximately $72 million. This work also provided local economic benefits through the sale of the harvested material, making the project mutually beneficial with a dramatic reduction in implementation costs.

Conceived in 2011, the project represented a partnership between cbec eco engineering, of West Sacramento, California; Teichert; Yuba County, California; and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The Yuba Water Agency joined the team in 2019 as the local implementation lead.

The project began with a feasibility study and an alternatives analysis to identify and assess potential habitat enhancement options on the Yuba River. This work was funded by Pacific Gas & Electric, which historically operated a hydroelectric facility at Englebright Dam. The funds were secured as part of mitigation of Pacific Gas & Electric’s hydroelectric project upstream and kick-started momentum on developing alternatives at the site.

In 2013, cbec — supported by two subconsultants, the South Yuba River Citizens League, of Nevada City, California, and Cramer Fish Sciences, of West Sacramento — received a grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Anadromous Fish Restoration Program through the longstanding Central Valley Project Improvement Act. This money supported planning, permitting, preproject monitoring, and design. A second grant from the Anadromous Fish Restoration Program was awarded in 2015 to finalize planning as well as to implement the first phase of the project.

The California Environmental Quality Act regulatory process was completed in winter 2017. Contracting and landowner negotiations occurred between 2018 and 2019.

Mapping and modeling

The project site spans 2 mi of the river and more than 150 acres. At the core of any project of this scale is the need to understand the interaction of physical and ecological processes to inform enhancement approaches.

To that end, accurate and current mapping of existing conditions was fundamental to design development and hydrodynamic modeling. Several topographic and bathymetric surveying efforts were conducted by cbec, including real-time kinematic GPS surveys of the floodplain areas, drone-based structure-from-motion topographic surveys, and bathymetric surveys. Compiled survey data provided a topographic base map for the overall project design and enabled the project team to compare the current analysis with prior lidar data to understand geomorphic changes at the site.

Field efforts conducted by project team members also verified the type and extent of vegetative cover to inform the bed roughness values used in the hydrodynamic model. Throughout the implementation of the project’s first two phases, the project team also collected drone aerial imagery to monitor progress from preproject to postproject conditions.

The key to understanding the dynamic environment of the project site involved the seasonality and range of flows as well as the resulting depths and velocities in the project area. For example, summer low flows are approximately 500 cfs; the two-year flows are 18,000 cfs; and the 25-year design flows are 128,563 cfs. With flow ranges of this scale, computer modeling is required to understand how design changes will affect the hydraulic conditions that provide suitable habitat for rearing salmonids.

The design involved the development and calibration of one- and two-dimensional hydrodynamic models to understand high flows and low ecologically functional flows, or flows intended to benefit a specific species and life stage by inundating expansive areas of suitable habitat.

The project team relied on the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Hydrologic Engineering Center River Analysis System software. Another key software tool was Sedimentation and River Hydraulics — Two-Dimensional, a flow hydraulic and mobile-bed sediment transport model for river systems, developed by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in collaboration with the U.S. Federal Highway Administration and the Water Resources Agency in Taiwan.

Skilled application of these modeling platforms helped the project obtain the Central Valley Flood Protection Board’s encroachment permit. It also assisted in the iterative design of the floodplain and channel grading, helped quantify project benefits regarding habitat suitability (a function of depth, velocity, and cover), and helped the design reduce the habitat conditions considered beneficial to salmonid predators.

Making the grades

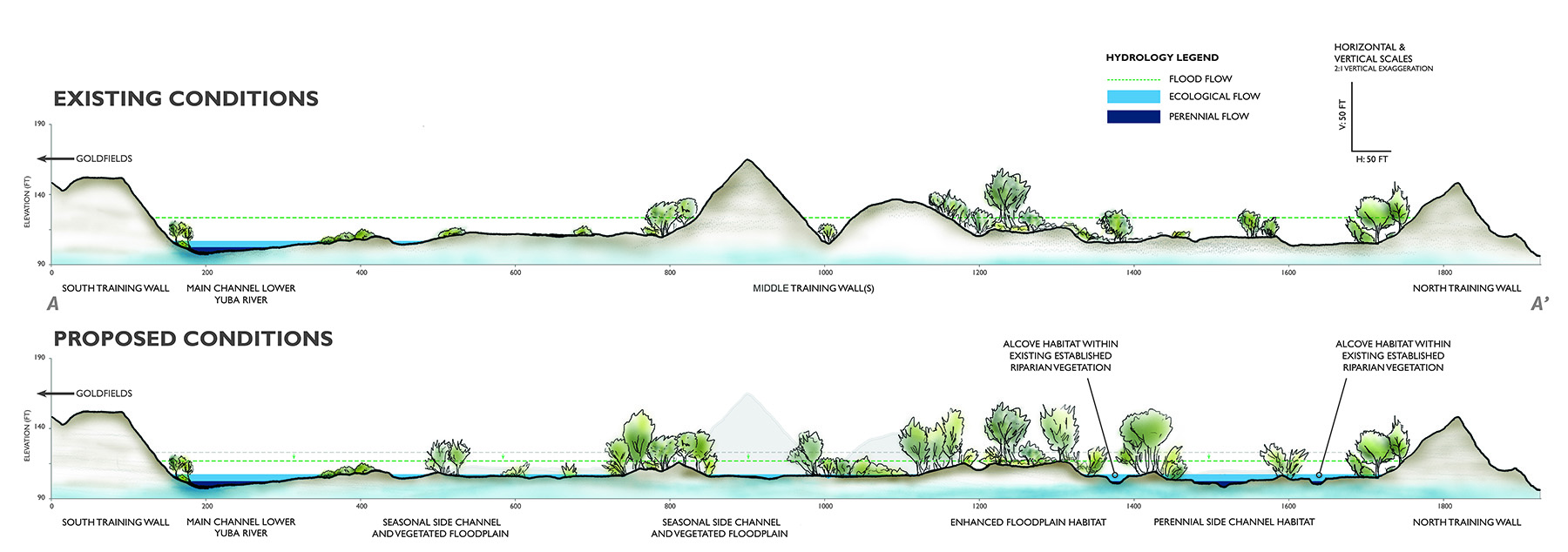

Grading designs were iteratively tuned with the hydraulic model results to develop the appropriate channel and floodplain elevations to function over a range of flows that coincide with the salmonid rearing period. These included a perennial channel, seasonal channels, backwaters and alcoves, and the overall floodplain.

A key aspect of a successful floodplain restoration effort is the success of naturally recruited vegetation and the revegetation of floodplain wetlands, scrub/shrub, and riparian forest habitats. Healthy riparian vegetation communities provide myriad ecological benefits, including cover, shade, and food resources for juvenile salmonids as well as other native species.

Existing floodplain plant species included elderberry, a species of concern as it houses the federally threatened longhorn beetle. Existing elderberry shrubs were geotagged and incorporated into the design; most existing elderberries were situated at the Middle Training Wall toe of slope. To minimize dust or root encroachment impacts to the shrubs, which could decrease available longhorn beetle habitats, mitigation measures were implemented.

These included fitting the grading edges in the field so as to avoid elderberry impacts and relocating some plants to increase the lateral floodplain connectivity through the retained vegetation zones at the Middle Training Wall relic toe. Key riparian planting species included Fremont cottonwood and native varieties of willow.

Getting the work done

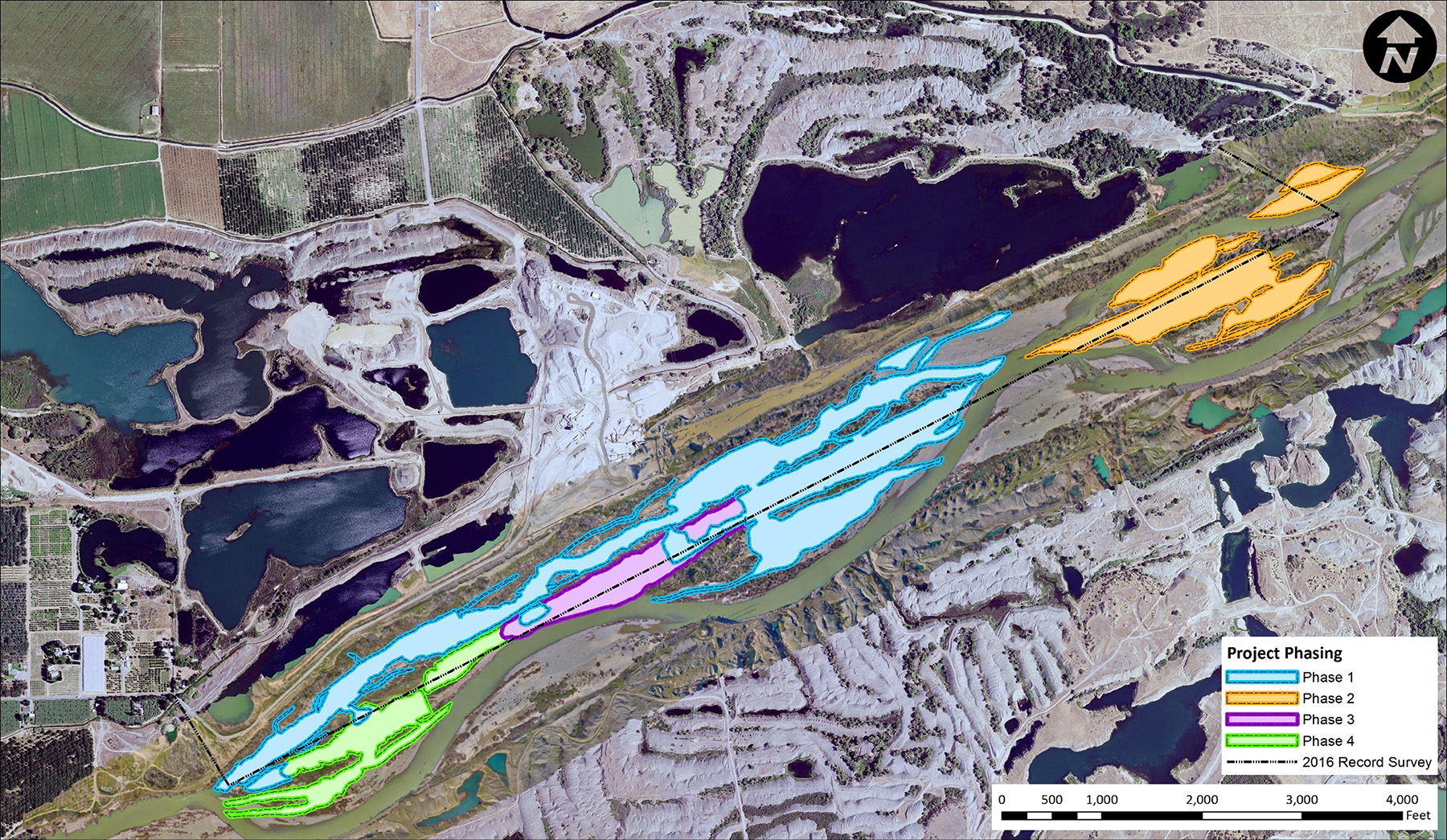

Construction of the project was limited to a permitted work window each year that ran from March 15 to Dec. 15. With the total project involving the removal of millions of cu yd of material, the project was divided into four implementation phases over an approximately five-year period.

Phase 1 began in August 2019 and was completed in November 2020. It involved coarse grading to remove the bulk of the Middle Training Wall and high elevation floodplain benches; fine grading to achieve finished grades of habitat elements, including channels, alcoves, and diverse floodplain topography; and riparian planting activities along portions of perennial channel edges and in select floodplain areas adjacent to seasonal channels. Ultimately, phase 1 removed 1.2 million cu yd of sediment, enhancing 89 acres of juvenile salmonid rearing habitat.

Phase 2 began in April 2021 and was completed in November 2021. It involved the removal of approximately 800,000 cu yd of sediment from the Middle Training Wall to reconnect the main channels to floodplain elevations across 34 enhanced acres. Phase 2 efforts created 1.5 mi of seasonal channels and planted about 12 acres of vegetation along seasonal channel margins. The work also included additional fine grading of phase 1 areas and the planting of approximately 26 more acres of riparian vegetation.

Phase 3 is scheduled for this year, and phase 4 is expected to be completed by 2023. These phases will remove more large sections of the Middle Training Wall, yielding approximately 815,000 and 400,000 cu yd of sediment, respectively. They will also enhance an additional 13 and 21 acres of floodplain and seasonally inundated side channel habitat, respectively. The estimated construction costs for the completed and future phases totals $6.8 million and covers fine grading, implementing large wood habitat structures, riparian plantings, construction oversight, and project management.

Funding has been secured for the remaining project phases through the Central Valley Project Improvement Act - U.S. Bureau of Reclamation/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Yuba Water Agency, and California’s Proposition 68 grant program — which addresses drought, water, parks, climate, coastal protection, and outdoor access issues — including funds allocated through the state’s Wildlife Conservation Board Streamflow Enhancement Program. In addition, support from U.S. Rep. John Garamendi, D-Calif., and his office facilitated the implementation of the project.

Overcoming challenges

As with any project of this nature and scale, there were unforeseen challenges. For example, the project site involved land owned by two competing aggregate production companies, Teichert and Western Aggregates, of Marysville. Access agreements between these firms required considerable care. In the end, an agreement was reached, thanks in part to the companies’ trust in the project team and a mutual desire to improve this reach of the Yuba River.

Prolonged spring flows, caused by water transfers to irrigators in the system, led to higher than anticipated early season groundwater conditions that required creative construction sequencing during the fine grading work. Fortunately, the end-of-season groundwater and flow-depth conditions were within target tolerances at the constructed riffle crests.

Emergency flow releases from Englebright Dam were required to support power generation. These releases precluded in-water work, shortening the construction window and requiring adjustments to the sequencing of the fine grading work.

River migration that occurred after the initial design phase forced changes to the perennial channel inlet design both prior to construction and during construction to provide passage for migrating salmon.

To acquire the volumes of large gradation riffle backfill material needed while staying within the construction budget, the project had to expand its material sources and adapt its sorting practices during the construction phases.

Bridging and digging

During phase 1 work, a temporary stream crossing spanning 50 ft was installed over an existing side channel to provide access to the Middle Training Wall and adjacent floodplain areas. Flow records were studied to assess potential flows during the construction window and define the threshold at which the bridge would need to be removed during a flood event. The bridge was constructed from temporary concrete abutments (known as K rails in California) and steel beams and plates to accommodate a conveyor as well as large, heavy equipment, such as scrapers, excavators, and bulldozers.

Front-end loaders and scrapers were used to excavate sediment, and the conveyor system removed excavated materials from the river corridor, significantly increasing project efficiency and reducing potential emissions to maintain a lower carbon footprint. On average, the coarse grading operations removed approximately 7,140 cu yd of material per day.

The grading work occurred concurrently in the historical overflow channel. Bulldozer, excavator, and articulated dump truck crews pushed high-elevation gravel deposits into a sequence of deep ponds in the overflow channel, where salmonid predators were observed during preproject biological monitoring. After lowering the floodplain in historically high-elevation areas, a low-flow channel was carved.

Historically, this overflow channel only inundated at the two-year flow recurrence interval. The new 1.7 mi long low-flow channel is 3 to 5 ft deep and 18 to 40 ft wide at base flow and is fed perennially by surface water, augmented with groundwater, and includes a sequence of riffles and pools. Numerous alcoves extending into retained stands of mature riparian vegetation also provide shade, cover, and food resources for juvenile salmonids.

After fine grading was completed, 5.3 acres of riparian vegetation was planted along the perennial and seasonal channel margins and on open floodplain areas to kick-start vegetation growth, sediment deposition, and the natural vegetation recruitment cycle, and to provide more immediate food and cover resources.

Winning all around

To date, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Yuba Water Agency are extremely pleased with the phase 1 implementation that was completed on schedule and within the contract budget. The biggest indicator of success is the target fish species’ response and indications of overall ecosystem health.

Monitoring of phase 1 conducted in spring and summer 2021 confirmed that rearing juvenile chinook salmon and steelhead were occupying the new habitats in the created channels. Spawning Pacific lamprey have also been observed, and macroinvertebrates have colonized aquatic areas. Riparian cuttings are leafing out, as are many woody and herbaceous plants that are naturally occurring across the graded floodplain areas.

For a project of this scale to be successful, it must provide benefits at multiple levels, which the Hallwood project does. Not only does the project provide a substantial amount of crucial habitat essential to the recovery of listed and special status fish species as well as a diversity of other organisms that benefit from a healthy river ecosystem, it does so in an extremely cost-effective way by leveraging a public-private partnership. Beyond the habitat benefits, the material removal provides substantial flood risk reduction, high-paying local jobs, and financial benefits to Yuba County through the taxation of aggregate sales.

Given the volumes of material to be removed from the river corridor, the unique team arrangement between cbec, Teichert, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Yuba Water Agency made the project feasible and led to low-cost implementation. The Hallwood project has shown that cost-effective floodplain and off-channel habitat rehabilitation can be realized through creative partnerships and well-chosen sites.

Nick Southall and April Sawyer are senior ecohydrologists; Sam Diaz, P.E., is a senior ecoengineer; Chris Hammersmark, Ph.D., P.E., M.ASCE, is a director and ecohydrologist; and Chris Bowles, Ph.D., P.E., M.ASCE, is an ecoengineer and the president of cbec eco engineering, in West Sacramento, California.

Funding is provided by the CVPIA - U.S. Bureau of Reclamation/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Yuba Water Agency, CA Prop 68, and CA Prop 1 via the CA Wildlife Conservation Board.

PROJECT CREDITS

Key project partners: Yuba County and Yuba Water Agency, Marysville, California; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Lodi, California, office; Teichert Aggregates, Marysville; Western Aggregates, Marysville

Primary project planner, prime consultant, and design engineer: cbec eco engineering, West Sacramento, California

Vegetation impact analysis and monitoring, planting plan design, and construction observation: South Yuba River Citizens League, Nevada City, California

Preproject biological monitoring, environmental permitting, pre- and during-construction biological monitoring: Cramer Fish Sciences, West Sacramento

Construction progress approvals: MBK Engineers, Sacramento

Cultural resources consulting: Horizon Water and Environment, Sacramento

Construction management services: The Handen Co., Rancho Cordova, California

This article first appeared in the March/April 2022 issue of Civil Engineering as “Golden Opportunity.”