By T.R. Witcher

The rugged Scottish Highlands remain a potent symbol of beauty, rich culture, and impassioned history. But while people might not currently think of a specific building as the architectural symbol for the country’s northern reaches, that may be about to change.

Perched atop a hill in the center of Inverness, the region’s largest city, the two buildings that constitute the current historic Inverness Castle — which has roots that stretch back almost a millennium — are in the midst of a multiyear refurbishment to transform the castle into a gateway for visitors to the scenic region with a turbulent past.

“The entire complex is going to become for (the) first time in its history a public building, a visitors center,” says architect Stuart MacKellar, a partner with architecture firm LDN Architects, which has been tapped to design the conversion of the castle. “Inverness is really the gateway to the Highlands. This is a natural gravitational point within Inverness.” The idea is that visitors will learn about the stories and voices of the peopleof the Highlands, and then be pushed out to different attractions and places of interest within the region, he continues.

The castle site’s earliest permanent use was an 11th-century fortification — and a series of castles have occupied the site since. According to the website of the Highland Council, the region’s governmental body, the first castle on the hilly site is “thought to have been built by Malcolm-Máel Coluim III of Scotland, who destroyed an earlier castle on a hill to the northeast, in which legend has it Macbeth of Scotland murdered Máel Coluim's father, Donnchad I of Scotland.” (Spoiler alert: Shakespeare later dramatized this tale in his classic tragedy, Macbeth.)

The existing castle consists of two buildings: a courthouse building, built in 1838, and an adjacent prison, built in 1848. The prison moved out in 1900, while the courthouse continued to serve as one until 2019. The Highland Council purchased the castle from the Scottish Court Service in 2019 with the intent to produce a master plan to redevelop the site.

Bloody history

The castle has served as a site of intrigue over the centuries. According to the council, James I summoned 50 Highland chiefs to the castle in 1428 for negotiations but then imprisoned or executed them instead. “One of those arrested was Alexander 3rd Lord of the Isles together with his mother, the Countess of Ross,” the council site explains. “After a year of imprisonment, he returned with 10,000 men and set fire to the city, though he failed in his bid to take the castle.”

In the middle of the 16th century, another castle on the site was “taken by the Clan Munro and Clan Fraser for Mary Queen of Scots during the Siege of Inverness (1562). She later hanged the governor, a Gordon, who had refused her entry.”

Before construction of the existing castle, the hilltop site served as a military barracks, but this was destroyed in the Siege of 1746.

Inside out

LDN and structural/civil engineering firm Narro Associates, one of Scotland’s preeminent firms specializing in historic preservation, have reconceived the buildings inside and out.

An earlier renovation had dropped a drab courtroom interior right into that building’s lobby, covering up its windows, main door, and grand staircase. All that architectural detail will again be visible after the project is complete.

New landscaping on a gentle southern slope that approaches the courtroom building will replace a parking lot and will including an accessible, switchbacking pathway. “We didn’t want it to appear as a segregated accessible route, (so) it’s woven into landscaping all the way up to the front door,” says MacKellar.

The redevelopment also calls for a 140 m long pedestrian walkway at the west side of the site, near the top of a steep slope that runs from the castle grounds down to a retaining wall, a roadway, and the River Ness. The angle of the slope and challenging soil conditions — the slope is riddled with rabbit holes — made even testing the soil conditions there difficult. Workers had to retrieve soil samples while in safety harnesses anchored to the walls at the top of the slope.

Ben Adam, CEng, FIStructE, FICE, a conservation accredited engineer and a managing director with Narro, said engineers considered digging out and terracing the foundation and building up from there, but trying to create safe working conditions meant the team would have to tear out almost all the soil before it could safely terrace.

Instead, says Adam, engineers devised around 60 mini piles to drill down to bedrock. It was a win for the rabbits — they could retain their existing burrows and establish new ones around the piles — and for the engineers: “We could bypass the pure soil, and the soil could settle, as we weren’t putting any extra pressure on it (with the construction),” says Adam.

Linking the castle buildings

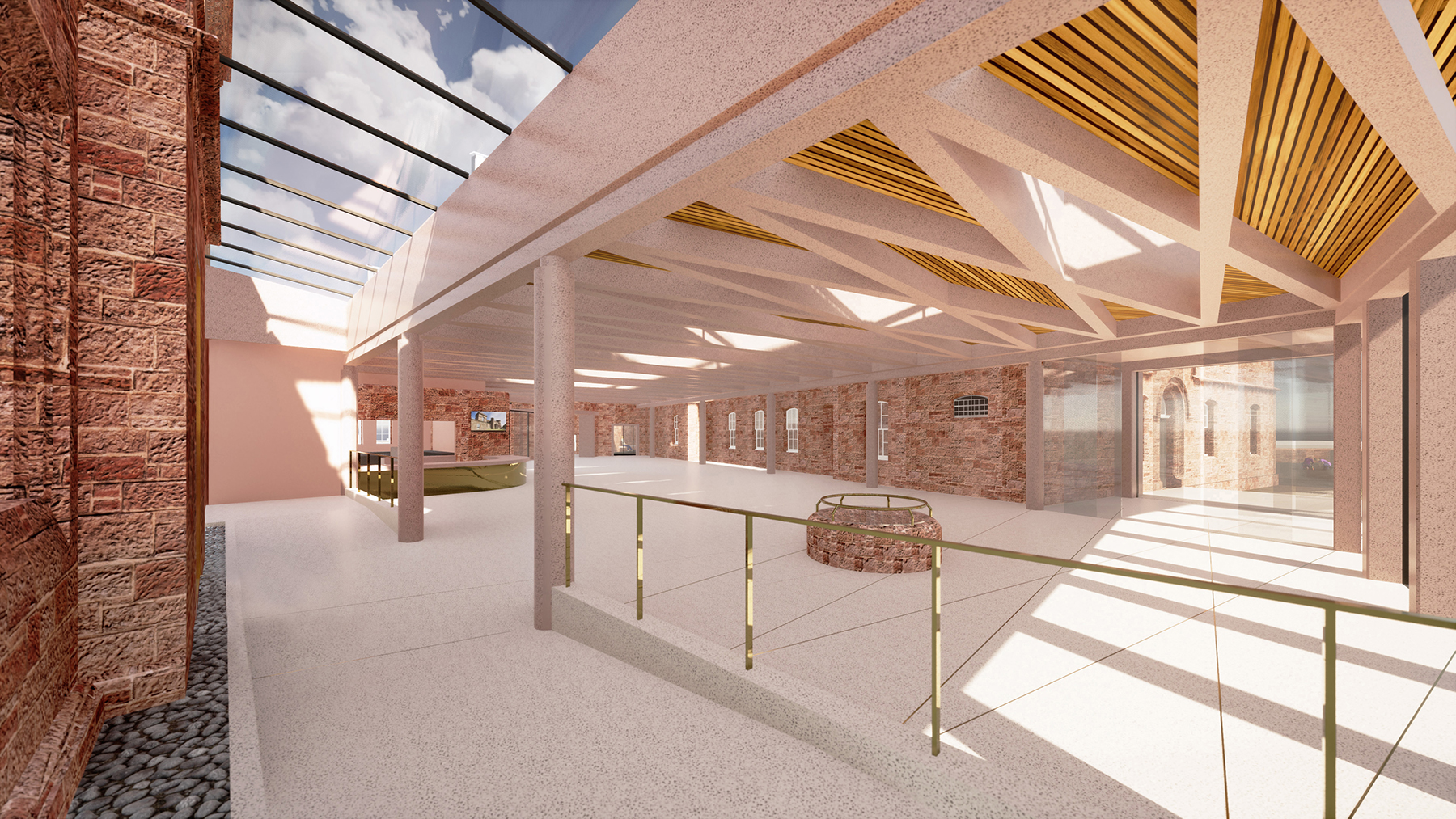

LDN also designed a building to link the old courthouse and prison. This link building, soon to be the largest interior space of the castle, is meant to be the central hub of the new complex and the place to meet friends for coffee.

To create the building, “we were effectively (just) designing a roof,” says MacKellar. This was because the existing castle buildings are situated such that they form three of the four sides of the new building’s boundary. The design team enclosed the space with a modest set of vertically proportioned windows — and saved its big design move for the space’s interior ceiling.

The link building’s roof is inspired by the interior of the castle’s courthouse building, which is defined by the exposed structures of its ceilings. “(We’ve) taken the geometry of the two buildings — they sit at an angle to each other — and we’ve struck perpendicular lines from both buildings and let them intersect in a saltire grid,” MacKellar explains.

These saltires — a diagonal cross like the St. Andrew’s Cross that adorns the Scottish flag — are cast-in-place concrete and create an elegant, diamond-shaped geometry, punctuated by a series of skylights and surrounded by a suspended ceiling of timber slats to conceal building services such as sprinklers and cabling.

“It was an absolute line in the sand for me; I didn’t want us to use any plasterboard,” says MacKellar. “It all had to be made from materials with a sense of permanence. It must feel like it’s been here for the same amount of time and will last for the same amount of time (as the existing buildings).”

The textured concrete aims to match the castle’s stone, which is made from red, aggregate-rich sandstone that adds character to the historic structure. “We were intent on (ensuring) the space between the building was going to be of similar quality and tactileness,” says MacKellar.

But engineering the roof posed a series of vexing questions. Adam says that there weren’t many high-end concrete specialists left in Britain to help plan the work (unlike in the 1960s, when brutalism was in vogue). LDN wanted the main roof to look like it was cast monolithically with no seams, which called for an in situ concrete pour. On the other hand, it made sense to make the concrete columns supporting the roof structure precast — as this would give builders better control of the product and could be put up faster and with a better finish. They even devised a U-shaped precast section across the column heads that could be filled in with an in situ casting of the roof.

But in the end, they opted to cast all the concrete in place to ensure there was consistency in the visual look of the concrete.

A final challenge confronting Narro was a planned upper roof terrace on the south courthouse building. LDN wanted to clad the outer walls and balustrade in corten steel, but Adam and his colleagues still had to figure out how to insulate and waterproof the structure. Narro proposed a corten “bathtub” to cover the entire terrace, with a standard steel secondary frame connecting floors, walls, and balustrades while not affecting a thermal or waterproofing envelope.

Further, Adam notes that the terrace sees huge wind uplift and the balustrades take high wind loads. “How do you stop that vibration and moving too much?” That vibration could impact exhibits in the interior space below.

To solve this, engineers devised a steel grillage that is below and behind the corten. The balustrades look solid by using corten panels, but they have hollow steel structures inside that allow the corten to be fixed together.

When asked about the complex work on the project, Adam said, “I want an architect to challenge us. That’s where the joy of the job comes from, and it always produces better results. And it gives us more of an opportunity to influence design.”

Insulating the castle

Insulating stone castles is challenging, says Mark Napier, ACIBSE, an associate with Harley Haddow, the engineering firm handling the electrical and mechanical work on the project. Harley Haddow, in conjunction with LDN, proposed adding insulation to the castle’s fabric as far as practicable, mainly concentrating on roof spaces, attic voids, and some floor voids.

“Some wall areas we can insulate with mineral fiber insulation with ventilation air gaps,” says Napier. But other walls, being part of the castle’s architecture, need to be exposed stonework.

Another phase of the project will also create a separate energy center building adjacent to the castle building — this facility will generate heating for the castle, Napier says, through heat pumps that pull in air and use it to heat water that in turn will heat the building. Down the line, as the area’s electricity grid becomes net zero, the building will become net zero as well.

As of publication time, contractors were about eight months into the 25 million pound (about $30 million), 2 1/2-year build to convert and restore both historic buildings, build the link building between them, and revamp the landscaping around the castle. Following the completion of construction, building out the interior exhibit spaces will take another six months.

The project should be completed and open to the public in 2025.

Future phases of the master plan entail the redevelopment of aging buildings or empty parcels adjacent to the castle to create a unified city district.

"This site has been the seat of power in the north, and it’s been fought over and a site of conflict for 900 years,” says MacKellar. “For the very first time it’s being handed to the public. It’ll be owned by the local authority and open to public for people to enjoy as a place to visit and learn about the Highlands. It’s a much bigger project than just the physical act of changing the building.”