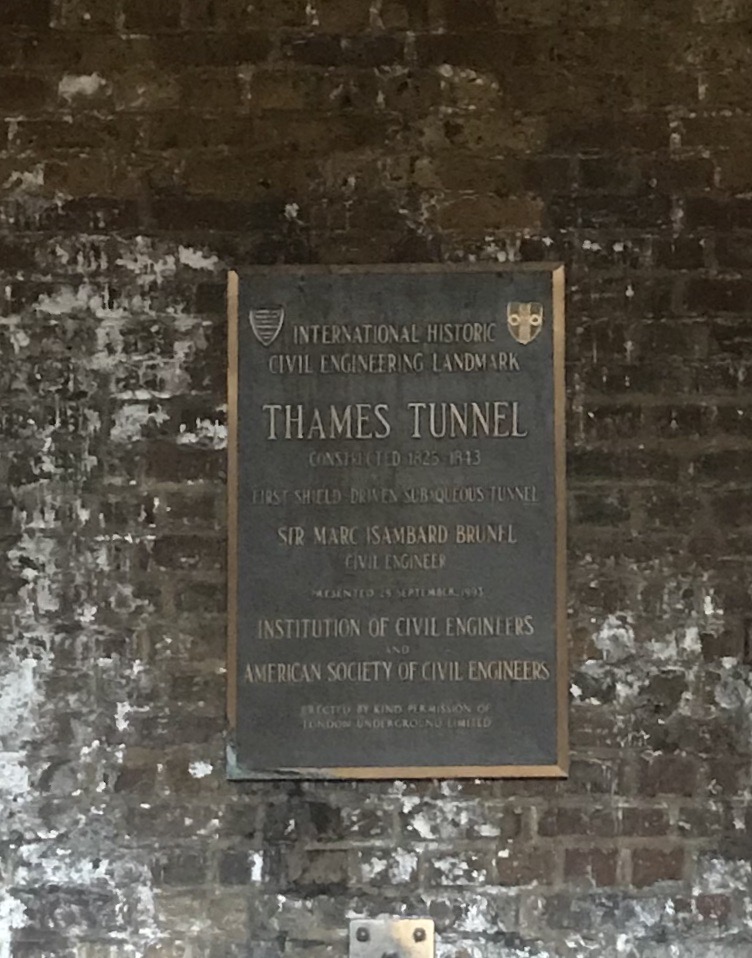

Thames Tunnel

51 30 12.7 N

0 03 13.3 W

The Thames Tunnel was the first shield-driven tunnel; the first successful soft ground subaqueous tunnel; and, in 1869, was adapted as the first subaqueous railway tunnel.

"...there is no work upon which the public interest of foreign nations had been more excited than it has been upon this Tunnel. Men cannot but see great political, military as well as commercial profit that will be derived..."

- Duke of Wellington, 1828

By the turn of the 19th century, London's streets were clogged with traffic. Over 3,700 passengers used the Thames River's main boat crossing each day, while wagons and carts were forced to cross via the London Bridge, two miles away. Building a bridge would further impede shipping on the already-crowded Thames; a tunnel was the obvious alternative.

The first attempt at a tunnel in the present location began in 1807. The excavation had proceeded only 1,000 feet-using traditional mining methods-when crews reached a layer of quicksand and were forced to stop.

But in 1818, Marc Isambard Brunel patented a revolutionary new tunneling device: a special rectangular, cast-iron shield that supported the earth while miners dug it away in small increments. Bricklayers would follow the shield, building a twin-arch brick tunnel lining as they went. Investors formed a new company to back the tunnel, and Brunel, with the assistance of his 20-year-old son Isambard Kingdom Brunel, eventually succeeded in building the Thames Tunnel.

Facts

- Prior to beginning the project, Brunel hired two civil engineers to take soundings across the river to evaluate the subsurface soil conditions. The soundings indicated the presence of a layer of blue clay, an ideal soil in which to build a tunnel. Shortly thereafter, in 1824, Parliament passed an Act allowing the tunnel to be built.

- The shield was comprised of 12 vertical sections. Inside each stood three workmen, one above the other. Each section had a stave on top to support the earth above. On the bottom there was a shoe attached to the frame that enabled the section to be slid forward by turning a large screw. On a good day, the tunnel moved forward by about three feet.

- Excavated earth was taken by wheelbarrow to a vertical shaft and raised to the surface by a windlass and bucket. Clay removed from the excavation was taken to a nearby brickyard where bricks were made for use in the construction.

- Work stopped on the tunnel for six years (1828 to 1834) for lack of financing after the shield ran into a gravelly layer of soil and the tunnel flooded.

- There are two tunnels, each 38 feet wide by 22 = feet tall, and 1200 feet in length. Located on the banks of the Thames, the shafts on either end of the tunnel are 50 feet in diameter.

- Although designed to accommodate vehicular traffic, the tunnel was initially open only to pedestrians. The East London Railway was formed in 1865 to take over operation of the tunnel. The first trains ran in December 1869, linking Wapping and New Cross Gate.

- The tunnel is still one of the most watertight tunnels on the London underground system. Apart from the new tunnel portals, it remains very much as it was when first constructed.