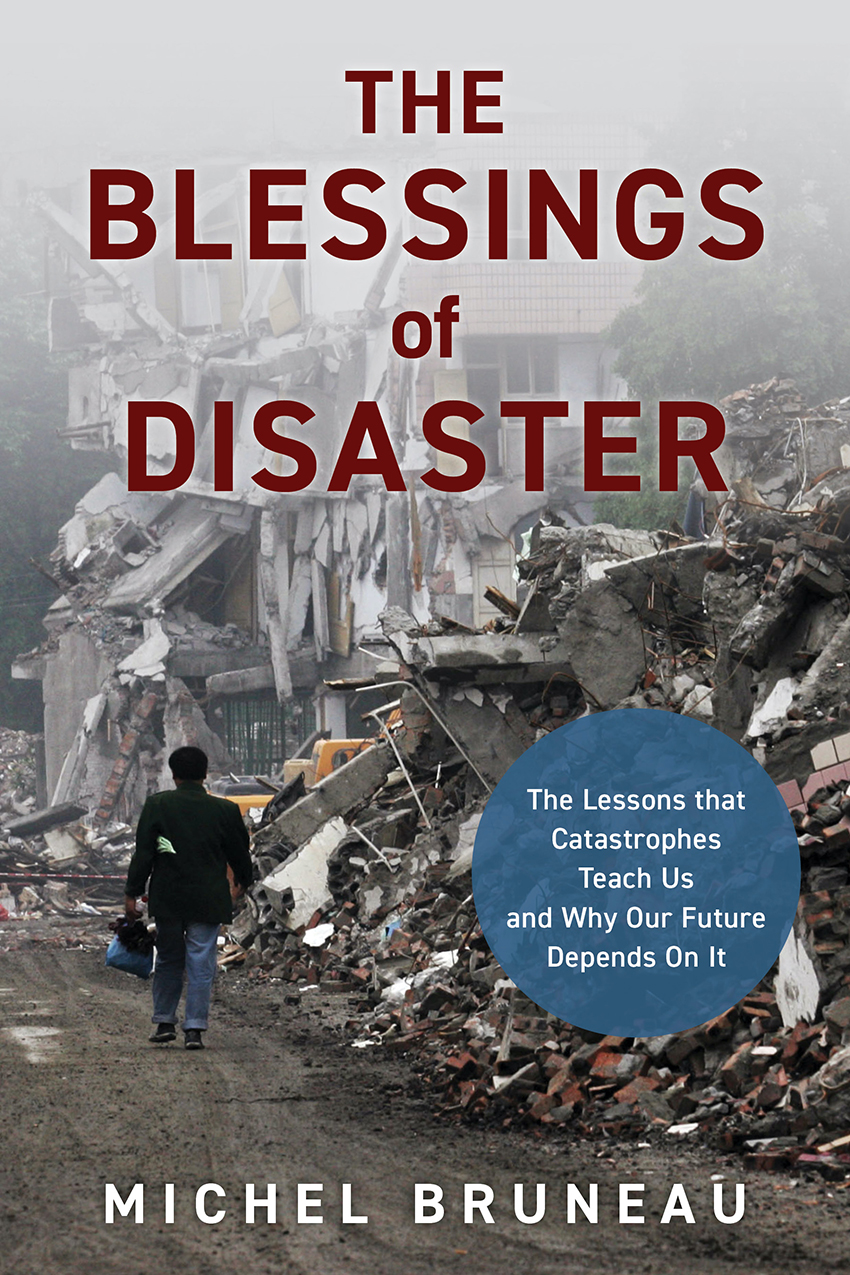

The Blessings of Disaster: The Lessons That Catastrophes Teach Us and Why Our Future Depends on It, by Michel Bruneau. Essex, Connecticut: Prometheus Books, 2022; 474 pages, $29.95.

In December, two urgent and potentially disastrous pieces of news came out in just one week. First, that due to drought, historic cuts in the amount of water taken from the Colorado River may be needed next year to avoid “dead pool” situations that could eliminate the ability of the Hoover and Glen Canyon dams to produce power and, even worse, severely limit the southward flow of water from the dams. Second, that after observing an Alaskan glacier front melting up to 100 times faster than previously assumed, researchers developed new computer models showing that the same could be happening to the Greenland ice sheet, the second largest in the world.

What do these two things have in common? Both are potential examples of foreseeable calamities that could come to pass after ample warning but insufficient appreciation of — or preparation for — the disasters themselves.

This is the subject of The Blessings of Disaster, by Michel Bruneau, Ph.D., P.E., P.Eng, F.SEI, Dist.M.ASCE. Why do humans so consistently underestimate the risk of disasters, only learning lessons after surviving them?

Bruneau is a University at Buffalo, State University of New York distinguished professor with primary expertise in earthquake engineering, particularly disaster mitigation. While earthquakes are a frequent metaphorical touchstone in the book — Bruneau notes that they “provide the perfect black-and-white contrast needed in case studies: they are sudden and devastating, but their threat is rapidly and conveniently forgotten during their long periods of quiescence” — the author’s thesis applies equally to many types of disasters.

To examine the question of why humans consistently underestimate risk, The Blessings of Disaster is arranged into three main sections.

The first introduces the reader to the wide range of potential hazards that many people around the world live with every day, such as tornadoes, floods, volcanoes, and more. Bruneau’s aim here is to show a certain universality of risk and threat and to explore examples of each.

The book’s middle section tries to answer the great “Why?” question. Why do people treat a small possibility as if it’s nonexistent? Why do they plan as if a clearly possible risk is instead unlikely?

The answer, according to Bruneau, is a stew of unrecognized brain biases; political inertia; lack of understanding of statistics, probability, and science; and other factors. Bruneau also shows that lessons are, in fact, typically learned in the wake of significant disasters. These lessons are the “blessings,” but they aren’t always permanent and they come at a steep price. But we can learn.

The book’s final section looks forward to potential future problems like overpopulation, climate-related disasters, global economic collapse, nuclear holocaust, and more and, in the author’s words, tries to answer the question: “Are we doomed?”

Bruneau’s complex answer essentially comes down to what the definition of “doomed” is. (Although Bruneau seems personally certain that nuclear war is inevitable, to him that does not equate to complete global annihilation.)

The Blessings of Disaster is an interesting and unique read: informative and well versed in research across many different knowledge areas but very often breezily informal and deliberately humorous in tone. But never at the expense of Bruneau’s realism; he has written a work that he hopes people will learn from — but, by his own admissions, knows they probably won’t.

“It is the exact thesis of this book that human nature cannot be changed easily,” he writes, “or, arguably, in some aspects, cannot be changed at all, barring a disaster.”

This article first appeared in Civil Engineering Online.